An American Explorer and Adventurer

Fourth Cousin, Seven Times Removed of Merle G Ladd

As a boy, John Ledyard grew up in thriving New London County, where the West Indian trade made fortunes for enterprising merchants and captains. But there were always risks, and when John was 11, his father, known as Captain John, and an uncle, Youngs Ledyard, died of disease while at sea. Young John and two cousins were sent to live in Hartford with their parental grandfather, the formidable Squire John Ledyard, who provided his grandson with room, board, and a solid education.

After Squire John's death in 1771, John became the ward of his uncle, Thomas Seymour, and apprenticed in Seymour's law office, but a different path opened for him in the spring of 1772 when he enrolled at Dartmouth. The college, the creation of former Connecticut preacher Reverend Eleazar Wheelock, had opened in the rustic New Hampshire woodlands just two years before. Arriving on 22 April 1772. He left for two months without permission in August and September of that year, led a mid-winter camping expedition, and finally abandoned the college for good in May 1773. Memorably he fashioned his own dugout canoe, and paddled it for a week down the Connecticut River to his grandfather's farm. Today, the Ledyard Canoe Club, a division of the Dartmouth Outing Club sponsors an annual canoe trip down the Connecticut River in his honor.

After leaving Dartmouth, Ledyard sought to launch a career in the ministry, making contacts in eastern Connecticut and Long Island, where his mother had settled after her remarriage. Failing that, he spent the year of 1773 as a merchant seaman, on the ship of Captain Richard Deshon, visiting the Barbary Coast and West Indies, returning to Connecticut in the summer of 1774.

In March 1775, just as revolution was about to erupt in the colonies, Ledyard boarded a ship to England where he enlisted in the British Army. Four months later, in July, he transferred into the British Navy, joining the Royal Marines as corporal .

British Royal Marine Uniform

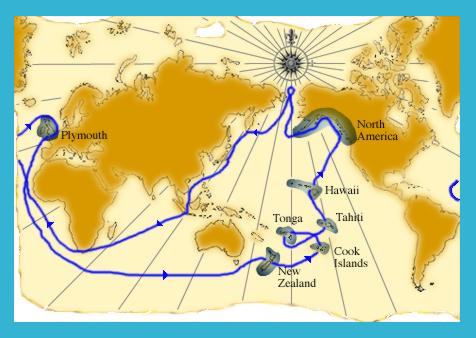

In June 1776, Ledyard joined Captain James Cook's third and final voyage as a British marine. During these four years, its two ships stopped at the Sandwich Islands, Cape of Good Hope, the Prince Edward Islands off South Africa, the Kerguelen Islands, Tasmania, New Zealand, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Tahiti, and then Hawaii (first documented by the expedition). It continued to the northwest coast of North America, making Ledyard perhaps the first U.S. citizen to touch its western coast, along the Aleutian islands and Alaska into the Bering Sea, and back to Hawaii where Cook was killed in February 1779.

He attempted to climb from Kealakekua Bay to Mokuaweoweo, the summit of Mauna Loa, but had to turn back. Then it was north, northwest to Siberia meeting Russian fur traders at Unalaska Island, south along the coast of China and Indonesia, touching upon Kamchatka, Macau, Batavia (now Jakarta), around the Cape of Good Hope again, and back to England.

His four years, two months, and 24 days spent at sea was the pivotal event in Ledyard's life. From Britain, the Resolution and its sister ship Discovery sailed south and east, around the Cape of Good Hope, across the southern Indian Ocean to Tasmania, New Zealand, and from there to the various Polynesian island chains of the South Pacific, where Ledyard was believed to be the first Euro-American to be tattooed.

The voyagers returned to England in October 1780.

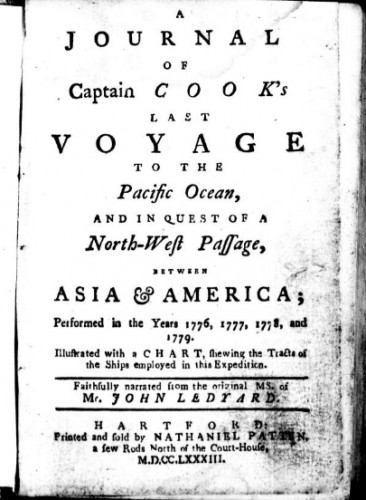

A Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage to

the Pacific Ocean by John Ledyard

Still a marine in the British Navy, Ledyard was sent to Canada to fight in the American Revolution. Instead he deserted, returned to Dartmouth, and began to write his Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage. It was published in 1783, five years after he had visited Hawaii, and was the first work to be protected by copyright in the United States. (It was in fact protected by Connecticut state copyright by special act of the legislature; federal copyright was not introduced until 1790.) Today, this work is annotated in rare-book bibliographies as the first travelogue describing Hawaii ever to be published in America.

His tale of Captain Cook's voyage was a best-seller in Connecticut and the newly-independent United States, and it led to some fame, but little fortune. The book's success was eclipsed by Cook's own three-volume "A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean", published posthumously less than a year after Ledyard's account. Cook's "official" account included a series of 87 engraved maps, charts, and illustrations. Ledyard's book had no illustrations except for one map.

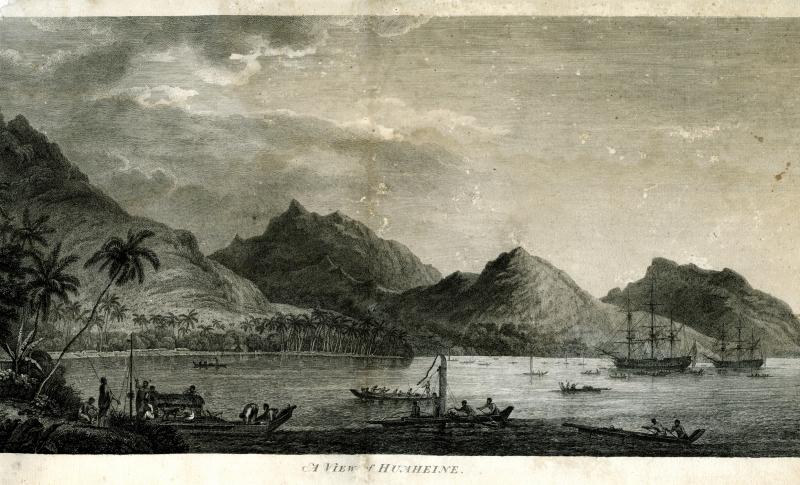

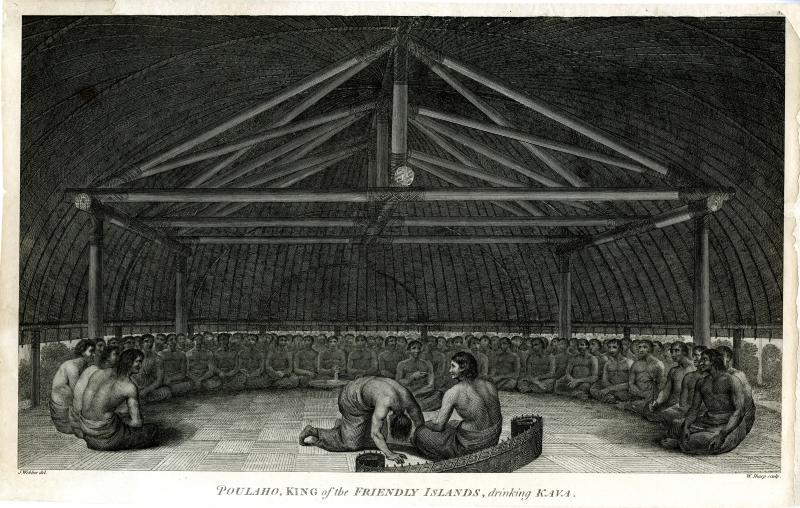

A Map of Captain Cook's Third Voyage

In 1783, the same year both books were published, Jeremiah Wadsworth, a successful merchant from Hartford, purchased Cook's volume in London; it's possible he sought it out after reading Ledyard's book. The engravings that came with the volume were unbound, and Wadsworth framed and displayed many of them in his home. In 1848 his son, Daniel Wadsworth, founder of the Wadsworth Atheneum, willed the engravings to the Connecticut Historical Society. Today, the engravings are accessible in the CHS Research Center. These vivid illustrations complement the adventurous narrative of Connecticut's own world explorer, John Ledyard.

A View of Huaheine. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, published 1783. Huahine, one of the Society Islands

in the South Pacific, was visited by Captain Cook in 1777.

Poulaho, King of the Friendly Islands, drinking Kava. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, London, published 1783.

Ledyard described Poulaho as "fat and corpulent, yet active and full of life... good natured and humane, very sensible and prudent."

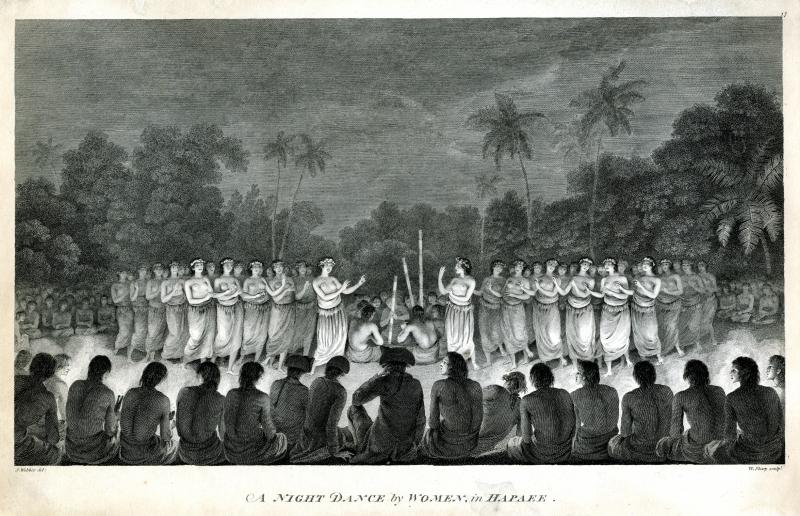

A Night Dance by Women in Hapaee. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, published 1783. John Ledyard may be one

of the three men seated in the center foreground, wearing a British officer's hat.

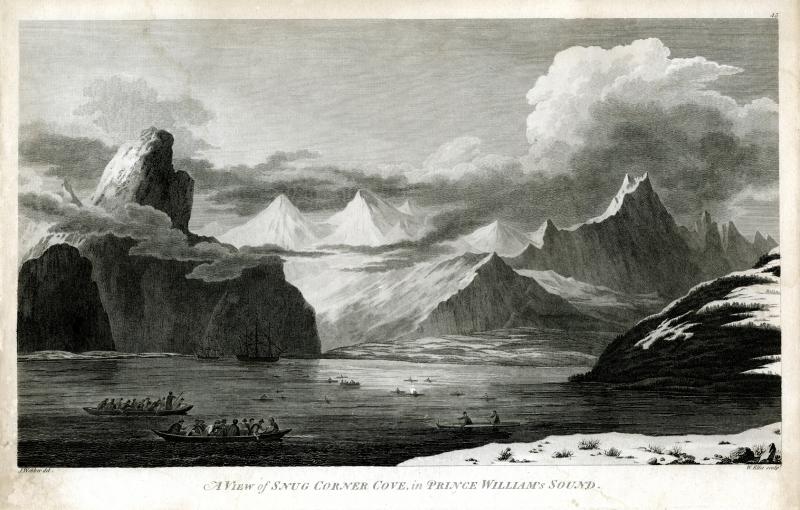

A View of Snug Corner Cove, in Prince William's Sound. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, published 1783.

Captain Cook and his crew explored Prince William Sound off the coast of Alaska in 1778.

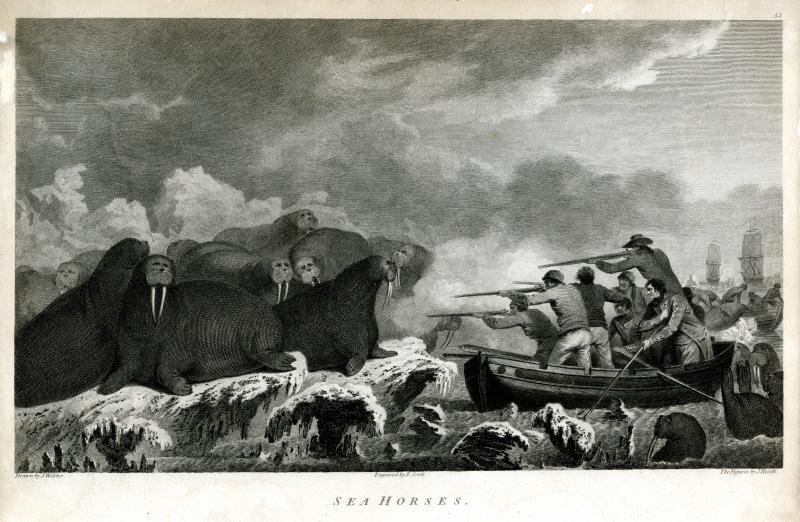

Sea Horses. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, published 1783. In his journal, John Ledyard described hunting

"sea-horses" (walruses) in the Arctic Ocean.

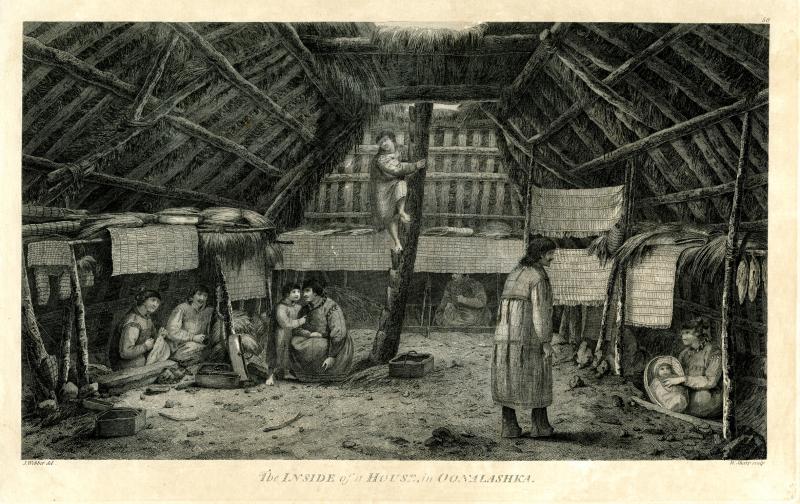

The Inside of a House in Oonalashka. Engraving after a drawing by John Webber, 1783. When Captain Cook called for a volunteer

to explore Unalaska Island alone, John Ledyard volunteered and was welcomed by Alaskan natives as well as Russian traders.

Francesco Bartolozzi, The Death of Captain Cook, 1784, engraving

Though portions of Ledyard's A Journal of Captain Cook's Last Voyage were later shown to have been plagiarized, perhaps by the publisher, and his supposed eyewitness account of Cook's death remains controversial, the journal remains a compelling document. Ledyard was a keen observer of the peoples and cultures he encountered, and his journal contains detailed descriptions of clothing, adornments, foods, and rituals.

Ledyard was quick to grasp the similarities of language and customs between far-flung groups of people. For instance, after meeting a group of Natives in what is now British Columbia, and calling upon his familiarity with native peoples from his Dartmouth days, he concluded, "I had no longer beheld these Americans than I set them down for the same kind of people that inhabit the opposite side of the continent." A few years later, he would record that, based on his own observations from deep within the Russian Empire, it appeared that Native Americans originally had migrated from Asia, a conclusion supported by many anthropologists and archaeologists today.

As Ledyard had noticed that sea otter furs from the American northwest commanded extremely high prices in Macau, he lobbied during the early 1780's for the formation of fur-trading companies. Ledyard suggested trading furs for Chinese silk and porcelain, which could then be sold in the United States. Although his partnership with Philadelphia financier Robert Morris was not successful, it did lay the pattern of the subsequent China trade.

Ledyard left the United States in June 1784 to find financial backers in Europe. He arrived in Paris in mid-1785. There he met Jefferson, Lafayette, and Benjamin Franklin and was drawn into the fabulous and seedy carnival that was life in the French capital in the last years of the Ancien Régime (The Ancien Régime was the monarchic, aristocratic, social and political system established in the Kingdom of France from approximately the 15th century until the later 18th century ).

In Paris, Ledyard conceived a remarkably bold scheme of exploration with encouragement from Thomas Jefferson, then American ambassador, and with financial backing from the Marquis de Lafayette, botanist Joseph Banks, and John Adams' son-in-law, William Smith. Jefferson suggested that Ledyard explore the American continent by proceeding overland through Russia, crossing at the Bering Strait, and heading south through Alaska and then across the American West to Virginia.

Ledyard left London in December 1786. He walks from Stockholm, Sweden, around the Gulf of Bothnia to St. Petersburg--arrives in St. Petersburg in March. He left St. Petersburg in June 1787 to travel through Moscow, Ekaterinburg, Omsk, Tomsk, Irkutsk, and Kirensk, reaching Yakutsk after 11 weeks, having hiked, hitched rides, and canoed across Siberia. Here he stopped for the winter but then returned to Irkutsk to join a larger expedition led by Joseph Billings (of the Cook voyage). However, Ledyard was arrested as a French spy under orders from Empress Catherine the Great in February 1788, returned to Moscow by approximately his original route, then deported to Poland

Chased out of Russia, Ledyard found his way back in London, he came across the African Association, then recruiting explorers for Africa. Ledyard proposed an expedition from the Red Sea to the Atlantic. He arrived in Alexandria in August 1788, but the expedition was slow to start. Late in November 1788, Ledyard accidentally poisoned himself with vitriolic acid (sulfuric acid) to treat enteric (intestinal) illnesses, and died in Cairo, Egypt on 10 January 1789. John Ledyard was buried in the sand dunes lining the Nile, in a modestly marked grave, the location of which is unknown today.

John Ledyard, one of the most adventurous figures in Connecticut's long history, would have made a great fictional character had he not been real.

Ledyard's passing saddened his many friends and admirers who included such luminaries as Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, the Marquis de Lafayette, and John Paul Jones. Jefferson himself helped cement his friend's posthumous legacy as Ledyard the Traveler. "...a man of genius, of some science, and of fearless courage and enterprise," Jefferson recalled in his 1821 autobiography. The two had met in Paris in 1786 and Jefferson had hoped Ledyard would become the first white man to traverse the North American continent, an accomplishment that might have eclipsed Jefferson's later Corps of Discovery, better known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition.